- Home

- Jon Pertwee

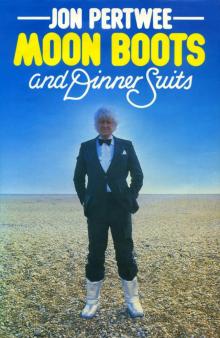

Moon Boots and Dinner Suits

Moon Boots and Dinner Suits Read online

Jon Pertwee’s acting career began with a public performance at the age of four. He seems to have been expelled from most of the schools his actor-writer father Roland Pertwee sent him to and finally joined RADA in 1936. From there too, he was asked to leave. Jon went into Rep and had a checkered career. In Brighton panic set in when he dresses as an old gardener in Love from a Stranger instead of as a young cleric in Candida.

In 1938 came Jon’s first radio role in BBC’s Lillibulero, in which year he also appeared in his father’s play, To Kill a Cat, directed by Henry Kendall at the Aldwych Theatre. When War came he joined the Navy ramming Douglas Pier with an Isle of Man Steam Packet boat. He was blown up twice, once being put on a marble slab presumes dead, and spent many months stationed in the Scapa Flow. He was the founder of the Service Players in the Isle of Man. He was commissioned in the RNVR and transferred to Naval intelligence where he worked and became good friends with the future Prime Minister James Callaghan. Then Jon joined Naval Broadcasting. His radio series, The Navy Lark, ran for eighteen years and produced some truly vintage memories of Radio.

Whether telling stories of a misspent youth, of his posterior’s first painful introduction to a fives bat or of his exploits with the McKenzie sisters in the north of Scotland, Jon Pertwee’s humour and natural wit never fail him. Moon Boots and Dinner Suits is a wry, funny and endearing portrait of the early years of a most innovative and well loved actor.

Jacket design by Pat Doyle; photograph by Nic Barlow

Photograph of Jon and Ingeborg Pertwee

on back of jacket by Brian Moody

© Scope Features

Moon Boots

and Dinner Suits

JON PERTWEE

ELM TREE BOOKS

London

For Ingeborg Without Whom . . .

First published in Great Britain 1984

By Elm Tree Books/Hamish Hamilton Ltd

Garden House 57-59 Long Acre London WC2E 9JZ

Copyright © 1984 by Jon Pertwee

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Pertwee, Jon

Moon boots and dinner suits.

1. Pertwee, Jon 2. Actors–Great Britain

–Biography

1. Title

792′.028′0924 PN2598.p/

ISBN 0-241-11337-7

Typeset by Rowlands Phototypesetting Ltd,

Bury St Edmonds, Suffolk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press) Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

My son Sean, who is dressed entirely by Oxfam and the Army Surplus Stores, has always regarded my penchant for elegant clothing as an embarrassing eccentricity.

When we were skiing in Andorra I said I would need to leave the slopes early, as Ingeborg and I were going to dinner with some friends and I would need to change. He raised his eyes to heaven and sighed, ‘Moon boots and Dinner suits as usual I suppose.’ I was about to administer an admonitory prod with my ski-stick when it occurred to me that this would be an excellent title for my book, so I stayed my hand.

I hope you will consider this merciful restraint to be justified.

I would like to thank George Evans for his help and for jogging my memory as it became necessary. I would also like to thank my friend Carl Hawkins. I don’t quite know why except that he would never speak to me again if I didn’t.

Introduction

I was told by my father about my first entrance as he was about to make his last exit.

Conceived on 11th November 1918, I’m the result of one joyful, victorious night. Yet I was the last thing my parents had expected or wanted!

Roland, my father, and Avice, my mother, had reached a sophisticated and amicable trial separation when they bumped into one another by chance, while celebrating V-Day amongst the jubilant crowds in Piccadilly Circus. I don’t know if it was the heady atmosphere of victory, or some nostalgic, rekindled passion which drove them into that fateful connubial embrace, but nine months later it produce an unwanted, instantly demanding and very noisy consequence, one Jon Devon Roland Pertwee – me! Jon after the apostle and disciple, Devon after the county, and Roland after my father.

The Pertwee is of French Huguenot extraction. According to our family tree, researched by a French Priest, one Abbé Jean Perthuis de Laillevault and my cousin the late Captain Guy Pertwee RN, the original family of Perthuis de Laillevault were directly descended from the Emperor Charlemagne, who ruled France in 800 A.D., and the line continues unbroken until the present day. The head of the family is Comte Bernard de Perthuis de Laillevault who fought with the RAF during the last war and is now a celebrated painter of murals.

After the Huguenot purge of 1685, the refugees fled to many countries including England where they settled mainly in Suffolk and Essex.

Norman Pertwee, the veteran tennis player and head of the Pertwee Flour and Flower Company in Frinton, is a direct descendant of the original Huguenot settlers, as am I.

Due to the inability of the English to pronounce the name Perthuis any other way than Pertwiss, it was subsequently changed to Pertwee. This proved a pointless exercise as over the years, even in England, I have been subjected to the following interpretations of my name, the veracity of which I will swear to, having avidly filed them away over the years : –

Tom Peetweet

Jon Peterwee

Jon Peartree

Mr Twee

Saniel Pertwee (A strange amalgam of my son and daughter, Sean and Dariel)

Mr Pardney

Mr Bert Wee

John Peewee (School, of course)

Newton Pertwee (Scientist?)

Mr Pickwick

Miss Jane Partwee

Master J. Peewit

Mr Pertweek

Joan Pestwick

J Pertinee

John Between

Mr and Mrs Jon Perkee

And the most recent addition, from a gentleman in Zimbabwe, assuming presumably that I am a “brother”. . .

J. Parpertwuwe

In the United States of America, however, I found that if you have a complicated, almost unpronounceable name of Lithuanian, German, Bulgarian, Russian, Czech, Japanese, Polish or Hungarian descent – a name Pztyltz for example – they will get it in one! But, if you happened to have a simple, honest-to-God name like Pertwee, they are utterly confounded!

I was playing on Broadway in There’s a Girl in my Soup when our ancient name received its final indignity. The stage door keeper of The Music-Box Theatre was sitting, cigar in face, guarding the keys, when I entered the stage-door.

“Hey Jan!”

As my Christian name is Jon, and as I was being proudly reminded of that fact by the regular sight of it emblazoned in letters of light on the Marquee above the Theatre, it was a natural assumption that the cigar-chewing voice was addressing somebody else!

The summons came again this time molto forte.

“Hey! Jan”

With puzzled expression and finger pointing at my chest, I turned, asking, “Who? – Me?”

“Yes! You! Jan Putrid! There’s a letter for you!”

Chapter One

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and woman merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. As, first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like a snail

Unwilling to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like a furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then the soldier,

Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the canon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well sav’d, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again towards childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sounds. Last scene of all

That ends this strange, eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans everything.

Jacques: As You Like It

Very few members of my profession can reach maturity in their careers without acknowledging the Bard in some way and so I’ve used Jacques’ speech ‘The Seven Ages of Man’ as a peg on which to hang the various hats I’ve worn throughout my life. The baby’s bonnet; the school cap; the velour snap-brim trilby with feathers – which I wore to woo my first love, the delicious Patricia of Caterham-on-the-Hill; the two naval hats which the government kindly gave me to put on during World War Two; and the ‘funny’ hat which I put on when I entered the theatre. Two of the pegs are still empty because I’m sure that none of my readers would be rude enough even to hint that I might be in my second childhood and, although my profession makes me something of a pantaloon, I am fairly lean – apart from a slight inclination to bulge around the midriff – and I’m not quite slippered yet.

First the infant, mewling and puking in his nurse’s arms! Well, I dare say I mewled a good deal and probably did my fair share of puking, though I hope I had the good taste not to do it actually in Nanny Hankins’ arms.

For some months after my birth, I led a happy, useful and productive life, lying in the nude on an astrakhan rug eating coal, preferring, I am told, the nutritious Welsh seam to the de-vitaminised anthracite nut! This will show that even at that tender age I was an infant of taste and discernment!

My mother, however, having take a good look at me and presumably not liking what she saw, divorced my father for his best friend, a romantic Frenchman named Louis de la Garde, and albeit temporarily, left the lives of my brother Michael and me.

Michael is three years older than me and very different, both in character and looks. He was a much better looking child with round blue eyes, and for a Pertwee an uncharacteristically short nose, slightly turning up at the end; his looks when he was older were often compared to the golden blond glamour of the then Prince of Wales.

With he and I now being left ‘motherless’, it was decided that we should go to live with my Granny and my Uncle Guy at their house in Caterham-on-the-Hill, Surrey.

At Caterham, having been successfully weaned from coal and waxed fat on to a combination diet of Glaxo, Robolene and Bengers, with the odd teaspoonful of Gregory Powder when the occasion demanded, I became so stout and sturdy that my poor Grandmother Emily, who used to take me on her knee to read me stories, swayed perilously when she subsequently tried to stand, my excessive weight having cut off the blood supply to her legs. In the event, she wisely decided that it would be better to wait until I had been put to bed, and sing me lullabies instead, a blissful experience, as having once been a concert singer of repute she could still tip a pretty stave.

My grandmother was a dear, plump, Victorian lady, whose husband Ernest, an architect and fey compiler and reader of verse, had died many years earlier. She was of medium stature, with a proud, jutting bosom whose cleavage was ever modestly covered by a piece of lace, and whose neck was always circled by a black velvet band, studded at the throat with intricate beadwork by day, and sparkling paste diamante at night.

She lived with her bachelor son Guy, spending winters in the town house in Campden Grove, Kensington that my father bought her, and summers in the country house in Caterham. Uncle Guy was a dear, kind, six foot celibate, with the hereditary nose of the Pertwees, referred to in the family as a ‘beezer’. His was original, in that it was built on a bias and had a curious kink to it, with, in winter, a permanent dewdrop hanging from its end.

He would start, stop, re-start, hiccup and backfire his way through a sentence, with an ‘I say, what? – now look here – er – can’t ever you do it? – no question! – do what you did – er – Mother, this was delicious, don’t you know!’

By profession, he was a teacher of elocution!

Frequently he travelled the country adjudicating at Eisteddfods and Girls’ High Schools, and subsequently had myriads of young ladies falling madly in love with him – a circumstance that afforded neither him nor the young ladies any satisfaction whatsoever!

Both he and my father were blessed with almost total recall. Ask ‘Unlucky’ what he was doing on Thursday 23rd October 1923, at 8:30 in the morning, and he would promptly recount, in exact and true detail, his breakfast, the headlines of his newspaper and the quality of his bowel movements!

This gift I sadly do not possess. If I did, it would have made the writing of this book a far easier task.

My earliest recollection of Caterham is one of complete and utter frustration on the lawn in front of the house. The sun was shining splendidly, and to get its full benefit I was imprisoned in my playpen, hot and fuming! After rattling all the rattles out of my rattle, hurling my stuffed bear at Mr Green, the gardener, and making many unsuccessful attempts at escape, there was only one thing left to do.

Calling my elder – and therefore ‘free-ranging’ – brother to my penside, I sweetly requested the loan of his finger.

Ever trusting, the gullible Michael did what was expected of him, and dutifully pushed it through the bars, whereupon I promptly grabbed it and bit it to the bone. Michael understandably did not enjoy this experience, but I did – enormously! It more that made up for my infuriating incarceration!

My father Roland used to visit us regularly at Caterham. He was the younger brother of my Uncle Guy, and another typical Pertwee – a tall, rangy man with bat ears, sharp features, that ‘beezer’ again, and a very ready wit to match! Although the background of his life was the theatre, he had started his career as a painter, but despite his considerable talent he seemed to lack the absolute dedication necessary for such a demanding profession.

As a very young man, he joined the Westminster School of Art, then moved on to Cope’s School of Art in South Kensington where he was granted a three-year scholarship at the Royal Academy School. In 1909, aged twenty-four, he went to Paris and studied at the famous Atelier Julien, which improved his work to such a marked degree that on returning to London, some of his portraits where accepted by the Royal Academy and were hung on exhibition.

After much heart-searching, he came to realise that painting was not a very lucrative profession and he decided to go on the stage instead. Sir Henry Irving’s son, H. B. Irving, gave him his first walk-on, but his big chance came when Violet Vanbrugh wanted a partner to appear with her in a duologue at the Coliseum. She chose my father and they appeared together on stage all over England for a year.

By then, my father had fallen in love and married my mother, Avice, and perhaps it was a combination of financial need and creative aspiration that made him start writing one-act plays, which were, at that time, regularly presented as curtain raisers to the featured play.

After the First World War, which he spent fighting in France, he was hospitalised for three months, during which time he wrote his first novel Our Wonderful Selves.

The next few years were eventful. He was divorced from my mother, he wrote, produced and was the leading man in his first full-length play I serve, which gav

e Edith Evans her first star part in London, and swiftly followed it with Interference, directed by Gerald du Maurier, and starring Herbert Marshall and Edna Best. Writing then claimed his time until he was eventually tempted to return to the stage by his old friend Gerald du Maurier in a play called S.O.S. His wife in the play was Gracie Fields, making, I believe, her only appearance on the ‘legitimate’ stage. She ‘died’ in the first act, and by the time my father came on, she was doing a Music Hall turn at the Alhambra, and by the time he was back in bed, she was singing at the Café de Paris!

Inevitably, Hollywood called, and he joined Warner Brothers as one of their principal scenario writers for several years.

I don’t remember my father ever showing me an over-abundance of affection – not that it was really expected in those days when parental love seemed to manifest itself in merely providing for one’s children according to one’s financial means and status. I shall always remember him as a somewhat remote figure who stepped in and out of my childhood shrouded with a vague indifference. When he married ‘D’ (of whom more anon) and we lived together as a family, he decided that his loyalty had to be with his new wife, who demanded a very different kind of respect and obedience from us that we had been used to when living with Granny. ‘D’ had little patience with my childish problems and tantrums, and my father’s apparent unwillingness to give me any moral support when ‘D’ seemed so obviously in the wrong offended my immature sense of rightfulness and justice.

Later, when I was working in Brighton Rep, he maintained this remoteness, in a most classic way. We were doing his successful murder mystery Interference and to the anticipatory delight of the Company, he agreed to come down and see the play. That night I peered through the front tabs until I found him sitting by himself in the Dress Circle, and duly told the anxious cast that he was indeed in front. Imagine my dismay when, after the show, he failed to come round backstage and I was left tearfully yet angrily alone in my dressing room, the rest of the Company, doubtful of the truth of his actual presence, having left.

Moon Boots and Dinner Suits

Moon Boots and Dinner Suits